Washington, D.C. – The Federal Circuit, sitting en banc, reaffirmed its rules of patent exhaustion in a 10-2 decision. It concluded that the Supreme Court decisions in Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc., and Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., did not require any change in the law of patent exhaustion. The 99-page decision was consistent with the position argued in the amicus brief filed by the American Intellectual Property Law Association.

Specifically, the Federal Circuit held that a patentee, when selling a patented article subject to a single-use/no-resale restriction that is lawful and clearly communicated to the purchaser, does not give the buyer, or downstream buyers, the resale/reuse authority that has been expressly denied. Explaining that the ruling in Mallinckrodt, Inc. v. Medipart, Inc., 976 F.2d 700 (Fed. Cir. 1992) remains unchanged, Judge Taranto wrote the following:

Such resale or reuse, when contrary to the known, lawful limits on the authority conferred at the time of the original sale, remains unauthorized and therefore remains infringing conduct under the terms of § 271. Under Supreme Court precedent, a patentee may preserve its § 271 rights through such restrictions when licensing others to make and sell patented articles; Mallinckrodt held that there is no sound legal basis for denying the same ability to the patentee that makes and sells the articles itself. We find Mallinckrodt’s principle to remain sound after the Supreme Court’s decision in Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc., 553 U.S. 617 (2008), in which the Court did not have before it or address a patentee sale at all, let alone one made subject to a restriction, but a sale made by a separate manufacturer under a patentee-granted license conferring unrestricted authority to sell.

The Federal Circuit also held that a U.S. patentee, by merely selling or authorizing the sale of a U.S.-patented article abroad, does not authorize the buyer to import the article and sell and use it in the United States, which are infringing acts absent authority from the patentee. Explaining that the ruling in Jazz Photo Corp. v. International Trade Comm’n, 264 F.3d 1094 (Fed. Cir. 2001), remains unchanged, Judge Taranto wrote the following:

Jazz Photo’s no exhaustion ruling recognizes that foreign markets under foreign sovereign control are not equivalent to the U.S. markets under U.S. control in which a U.S. patentee’s sale presumptively exhausts its rights in the article sold. A buyer may still rely on a foreign sale as a defense to infringement, but only by establishing an express or implied license–a defense separate from exhaustion, as Quanta holds–based on patentee communications or other circumstances of the sale. We conclude that Jazz Photo’s no-exhaustion principle remains sound after the Supreme Court’s decision in Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 1351 (2013), in which the Court did not address patent law or whether a foreign sale should be viewed as conferring authority to engage in otherwise infringing domestic acts. Kirtsaeng is a copyright case holding that 17 U.S.C. §109(a) entitles owners of copyrighted articles to take certain acts “without the authority” of the copyright holder. There is no counterpart to that provision in the Patent Act, under which a foreign sale is properly treated as neither conclusively nor even presumptively exhausting the U.S. patentee’s rights in the United States.

Judge Dyk filed a dissenting opinion, which was joined by Judge Hughes, that generally agreed with the position argued in the government’s amicus brief.

With respect to Mallinckrodt, Judge Dyk maintained that the decision was wrong from the outset and cannot now be reconciled with the Supreme Court’s Quanta decision. “We exceed our role as a subordinate court by declining to follow the explicit domestic exhaustion rule announced by the Supreme Court,” he added. With respect to Jazz Photo, he wrote that he would retain the ruling if read to say that a foreign sale does not always exhaust U.S. patent rights, but it may if the authorized seller failed to explicitly reserve those rights.

Background

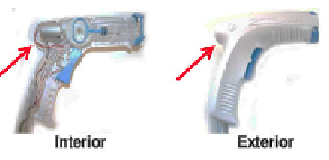

Lexmark makes and sells patented ink cartridges for its printers. It sells cartridges under one plan that permits buyers to use them as they wish, and at a discounted price under a “Return Program” plan that limits buyers to a single use of the cartridge and requires the cartridges to be returned to Lexmark for recycling.

Lexmark brought infringement actions in the district court and the International Trade Commission against Impression Products and other makers of after-market ink cartridges for Lexmark printers. Most of the district court defendants settled the litigation with Lexmark.

As to Lexmark’s action against Impression Products, the district court entered a stipulated judgment on Impression Products motion to dismiss. It held that Lexmark’s patent rights in cartridges first sold in the United States were exhausted under Quanta, but that the rights were retained for cartridges first sold abroad under Jazz Photo.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit sua sponte granted en banc review of whether the appellate court’s ruling on conditional sales in the U.S. must be overruled in light of Supreme Court’s Quanta decision, and whether the appellate court’s Jazz Photo ruling on international exhaustion must be overruled in light of the Supreme Court’s ruling on copyright exhaustion in Kirtsaeng.

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News

Indiana Intellectual Property Law News